Tim has social anxiety disorder, which affects about 4% of young Australians.

His social anxiety started to develop when he was around 18 years old, which is an age where the initial development of social anxiety is common (in fact, there are two peaks of incidents: 11-15 years of age, and 18-25 years of age).

When looking at these two age ranges, it makes sense why anxiety disorders are commonly birthed there. These are periods where physical, social, and educational changes are sudden and dramatic — between the ages of 11 and 15, puberty takes place, and from 18 to 25, people are expected to take on unprecedented levels of independence – think post-secondary school and/ or work, sometimes with little guidance.

These are stressful times, and different brains respond in different ways.

For Tim, heading off to uni was the onramp to his ongoing struggle with anxiety. After graduating from high school, he was really looking forward to starting his degree. He was going to spend the next 4 years in a coastal Australian city surrounded by smart and hopefully fun people from all walks of life.

But when he arrived on campus, he felt a strange feeling of isolation and fear that he first attributed to “new beginning jitters.” He understood that nervousness was a normal part of any new chapter (especially when it comes to meeting new people), so he brushed off his inability to connect with others as typical growing pains of a new uni student.

However, as the days became weeks and the weeks became months, his initial bout of “new beginning jitters” morphed into something entirely different. While he felt somewhat comfortable with his roommate, his mind and body would experience almost unbearable levels of fear and anxiety when faced with various social situations.

Whenever Tim would meet someone for the first time or hang out with an unfamiliar acquaintance, his heart rate would rapidly increase, causing his chest to tighten up as tension swept through his entire body. This overwhelming feeling of dread would start from his heart and quickly make its way to the top of his head, causing his mind to race violently in the process.

As he would try to converse with a stranger — let’s call her Stephanie — his mind would spew out thoughts at a frantic and chaotic manner.

Anxious thoughts quickly bombard his mind as a response to his uncomfortable physiological sensations, causing them to grow even stronger. As these sensations intensify, Tim avoids eye contact with Stephanie as much as possible, believing that she will judge him for being the anxious wreck that he is. He tries his best to carry along the conversation, but believes that he is being judged every step of the way.

However, the reality is that no one is really judging him, and Stephanie is genuinely excited to meet Tim. She’s heard a lot of great things about him, and just wants the opportunity to get to know him better. She doesn’t really notice all the things that Tim is experiencing, and even if she did, it doesn’t matter to her because she believes that she’s engaged in good conversation.

But even if Tim knew all this, it would be difficult to feel reassured because all these physical sensations are telling him otherwise. Despite him knowing that this conversation is not a life-or-death situation, his mind and body are automatically reacting to her presence as if it were just that. These physical discomforts (rapid heart rate, flushing of the face, etc.) are giving way to an emotional interpretation of them (fear, dread, embarrassment), thus solidifying themselves into a behavioural response of avoidance.

These sensations are the result of neurobiological processes that are happening within his brain, and they don’t have anything particularly wise to say about the narrative of his character. In order to break the link between these physiological sensations and his behavioural response to them, it’s important to take a look at what’s going on underneath the hood. When we’re able to understand the automatic processes that happen here, it becomes easier to disassociate ourselves from the thought that our anxiety defines who we are.

So what we’re going to do now is zoom in on Tim’s brain. That impossibly intricate, complex mesh of neurons, cells, and tissue is making Tim feel terribly petrified at the sight of Stephanie’s presence.

What exactly is happening here when Tim’s social anxiety kicks in? How does an external social cue / stimulus cause his body to instantaneously tense up and sweat profusely?

The Biology of the Anxious Brain

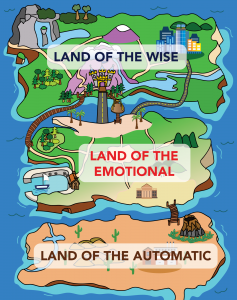

A useful model in providing a high-level view of the brain is Paul MacLean’s triune brain model. It breaks the brain down into three metaphorical (not literal) layers, with each section having a group of components working together to achieve a greater function.

Using this model as our navigational tool, let’s imagine the brain as if it were a world divided into three interconnected islands:

(1) Land of the Wise

(2) Land of the Emotional

(3) Land of the Automatic

There’s a lot going on in this wild amusement park, as each continent has its own inhabitants and gears that allow the whole system to work. We will soon visit each one, but in an order that follows how an external stimulus is processed through each of the lands to create the dreadful feeling of anxiety.

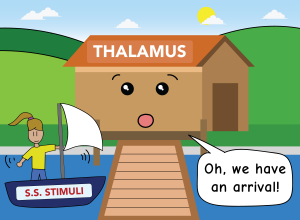

Before we begin the tour, let’s rewind the tape to seconds before Tim meets Stephanie. They will meet shortly, and Stephanie will become the external stimulus that pushes Tim’s anxiety into full gear the moment it happens. So in the context of our map, Stephanie is the passenger aboard the S.S. Stimuli, the boat that is headed toward Sam’s awaiting brain.

The S.S. Stimuli’s destination is the Land of the Emotional, which is where we will begin our tour.

The Land of the Emotional

The Land of the Emotional, or the LOE, is better known as the brain’s limbic system. The term limbic system comes from the Latin word for “ring,” which refers to the structures that ring around the upper part of the brainstem.

The limbic system is responsible for taking in external stimuli, initiating involuntary responses to them, and assigning emotional significance to them afterward. It is the part of ourselves that we jokingly call “our monkey brain”, where impulsive behaviour and automatic responses to our environment can reign supreme.

It’s also the part of our brain that evolved to make us feel fear when we see a lion, arousal when we check out an attractive person, and hunger when watching someone eat a delicious meal. The LOE has allowed us to use pleasure and fear as tools to propagate the human species, but if left unchecked, it can lead to a significant number of problems.

The LOE is our starting point here because this is where the brain first receives the S.S. Stimuli. And the place it does this is at the port of the thalamus, which acts as the relay station for incoming information from the external world.

Upon receiving a stimulus, the thalamus makes an instantaneous evaluation of it, then sends its results to two primary places:

(1) The amygdala (which resides in the Land of the Emotional as well), and

(2) The Land of the Wise.

The amygdala will make its grand entrance shortly, but it’s important to remember that the thalamus also sends its information to the Land of the Wise as well. However, since the amygdala lives right next to the thalamus, it receives sensory information faster than the Land of the Wise does (in fact, the neural pathway from the thalamus to the Land of the Wise is literally longer than the one going to the amygdala). This will be very relevant when we begin discussing the function and characteristics of the Land of the Wise in the next post.

So in Tim’s case, the thalamus has received Stephanie’s face as an external stimulus, and has passed that information along to the next character, the amygdala. The amygdala is one of the central characters in initiating the brain’s anxious response, so let’s take some time to explore this odd thing.

The Amygdala

The amygdala is the reason why the Land of the Emotional is just that… an extremely emotional place. The amygdala acts as the brain’s early warning system, and assigns emotional significance to incoming information from the thalamus. And since it’s the first part of the brain to produce a reaction to this stimulus (the specific area of note is the lateral amygdala), it is the pivotal character to much of the emotion behind fear and anxiety.

The desire to fit in with a group is deeply embedded in our brains, so when the risk of being a social outcast is high, the amygdala freaks out and sounds the alarm. This fear of being “the other” is undeniably tied to social anxiety, where its sufferer is under the continuous assumption that he is not exhibiting behaviour that would make him like-able.

This is what happens when Tim’s amygdala receives information about Stephanie’s status as a stranger. Tim’s amygdala has been conditioned to treat unfamiliar faces as threats to his survival, so Stephanie’s presence causes it to prepare other parts of the brain for an instantaneous stress response.

As the amygdala sends its alarmed response over to another player in the Land of the Emotional (who we’ll get to shortly), I want to pause for a moment and draw your attention to the Hippocampus, who is feverishly recording everything that’s going on in the background.

The hippocampus is vital for the development of memory, and it pairs the details of a situation with the emotion that the amygdala generated for it. It feverishly writes down all the events and emotions of the day on a big scratchboard, and when the day is over, it will deliver this up to The Land of the Wise for memory storage and processing. During the all-important REM sleep cycle, the insignificant details of life are discarded, and significant information is stored as long-term memory. This process will then free up the hippocampus’ scratchboard, which allows it to record all the details and events of a fresh new day.

So if the sight of Stephanie’s face got Tim’s amygdala all worked up, the hippocampus will record that fact, and will process it as a significant event for the day. As a result, unfamiliar faces can be tagged as fear-inducing stimuli for Tim, regardless of whether or not Stephanie continues to be the unfamiliar face in question.’ It can be any stranger that causes it due to the emotion associated with that encounter — this is why anything that can remind someone of a traumatic event (a smell, a sound, etc.) can elicit the stress response that was experienced during the actual event itself.

The hippocampus’ role as a record-keeper is important to remember as we continue this tour of the anxious brain — if we can determine how to “unlearn” the fear associated with an external stimulus, the hippocampus will also keep track of that fact too. Any progress or work we do toward treating anxiety will also be recorded by the hippocampus as well, which is a great thing to be mindful of when addressing it head-on.

Okay, now that we’re aware of the hippocampus’ background omnipresence, let’s get back to the amygdala.

At this point, the amygdala has interpreted Stephanie’s presence as an immediate threat, and wants to initiate the body’s stress response to prepare it accordingly. The famed fight-or-flight response is the body’s way of putting you in a state of alertness to address a stressful situation — whether the stimulus is a hungry mountain lion or an unfamiliar human face, the body will go through the same motions to prepare you for it.

The pathway to a physical sensation starts with a character living in the Land of the Emotional, but it lives in an embassy representing another continent: the Land of the Automatic.

The amygdala has alerted the ambassador living in this embassy, who is none other than the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus takes the fear alert from the amygdala and translates it into a message that the Land of the Automatic could understand. It does this through the release of something called the corticotropin release factor, which will kick off a series of events that leads to all the unpleasant sensations associated with intense anxiety.

To see what happens next, let’s now head south, where we’ll see how the hypothalamus’ message translates into the formation of the stress response.

The Land of the Automatic

The Land of the Automatic (“LOA”) is an ancient and primitive place — I imagine it to be the desert ruin of the human brain.

In Paul MacLean’s triune model, the LOA is known as the “reptilian” part of the brain — it’s the part of our brain that regulates automatic functions like heart rate, breathing, blood pressure, temperature control, etc. — essentially, it’s the engine that keeps the brain working without asking too many questions.

Although the LOA seems very mundane on its surface, it plays a huge role in the creation of uncomfortable sensations for those with anxiety problems. When the hypothalamus is alerted to initiate the stress response, it will start a process known as the HPA axis, resulting in the release of that infamous hormone known as adrenaline. Adrenaline will stimulate the body by increasing the heart rate, elevating blood pressure, and increasing respiration levels , triggering what is known as the sympathetic nervous system (SNS).

While adrenaline is released in high levels during this state of arousal, there is another important player living in the LOA that is responsible for even greater levels of discomfort brought forth by anxiety. The specific place of interest here is the pons, which is located in the brainstem. It typically deals with boring things like swallowing, facial sensations, posture, and so forth, but there’s a landmark here of particular interest: the locus coreuleus.

The locus coreuleus is a factory that can receive information directly from the amygdala, and it manufactures one primary product of importance: norepinephrine. Norepinephrine is the key that unlocks all the heightened physical responses you feel when anxiety hits you like a ton of bricks. It’s a neurotransmitter that triggers many of the immediate signs of social anxiety — sweating, blushing, tremors, heart palpitations — and is poured out in droves when the sympathetic nervous system is turned on.

For those with social anxiety disorders, an excessive release of norepinephrine kicks the sympathetic nervous system into overdrive, and can lead to the sensation of “freezing” during a social anxiety attack. This is when your mind goes completely blank during the middle of a conversation, and nothing comes to mind to bring things back on track. As you can guess, feelings of shame and embarrassment are commonly felt during this shitty experience, and can intensify one’s fear of being in a social situation again.

As adrenaline and norepinephrine are released in droves throughout Tim’s nervous system, keep in mind that the hippocampus (the record-keeper of the brain) is logging all of this down, associating Stephanie’s presence with the unpleasant sensations of the fear response. Since the hippocampus’ job is to link an emotion with a stimulus, tagging Stephanie as an “unpleasant threat” seems like the logical thing to do, given all the havoc she’s caused for his nervous system.

In many ways, we tend to think like the hippocampus does. We only see the beginning point (the stimulus) and the end result (the triggering of the stress response), and immediately associate causation between the two. However, the reality is that there is an intricate chain of neurobiological processes that occur for the stimulus to eventually create this response.

In summary, the process is this: The stimulus first reaches the thalamus, which relays this information over to the amygdala. The amygdala quickly interprets the response as threatening so it alerts the hypothalamus, kicking off a multi-step process that produces adrenaline and norepinephrine. This then fires off the sympathetic nervous system, which finally creates the sensations of chest tension, sweaty palms, and lip quivers that makes Tim feel so anxious and scared.

There’s a lot going on here, but unfortunately, it all happens within a fraction of a second. And because it happens so quickly, we end up lumping together all of these individual players and processes into a singular amorphous feeling – and call it anxiety. When we do this, it becomes difficult to face this overwhelming blob directly and find ways to manage it mindfully. It’s like being the head coach of the Lakers and saying that your gameplan for beating the Warriors is that you’ll “just find a way to beat the Warriors.”

A coach doesn’t view the opponent as a singular team that moves as one massive unit — no, he breaks down the opponent into individual players, studies each person’s strengths/weaknesses, and analyzes the relationships they have with other players on the team to understand how they all work together. Breaking down the team into individual components is the only way to figure out how to face the team as a whole.

Similarly, learning about the biology of the anxious brain allows you to break down the feeling of anxiety into smaller players that can be identified and targeted. What was originally perceived as a “feeling of fear and unworthiness when meeting a stranger” can be reframed as an “overreactive amygdala that has incorrectly perceived this stranger as a threat.” The thought that your sweaty and flushing face “is due to social incompetence” can be reframed as the result of an “automatic norepinephrine release that can be calmed down.”

When we learn how to attribute these unpleasant sensations to known biological processes, our emotional interpretation of them shifts accordingly. The more we can train our brains to know that these sensations do not signify anything meaningful about the quality of our character, the more we can adjust our behavioral response to readily enter situations that would generally elicit discomfort.

So where do we go to start this process of reframing our minds? How do we modify the incorrect beliefs that anxiety may have improperly installed?

Well, now is the right time to set our sights north and head on over to the highest land on our map of the brain. We’ve spent a good amount of time in the Land of the Emotional and the Land of the Automatic, but when it comes to making rational choices and executive decisions, these places aren’t equipped with the proper terrain to do that.

Instead, we need to visit the outermost layer of the brain, where all the magic happens. This is the most recently evolved part of our brain, and is responsible for handling cool things like reasoning, decision-making, abstract thought, and executive function. It also has the amazing power to override the functions of the other two lands that we’ve already visited, and it actually does this quite regularly.

To illustrate this, let’s pause for a moment to take a nice, deep breath. Allow the cool sensation of the breath to enter through your nostrils …and follow it as it ends in a relaxing exhale out of your nose or mouth. That deceptively simple action right there is this magical land at work. It overrode the unconscious pattern of breathing that the Land of the Automatic usually controls, and commanded it to take a backseat for the time being.

To put it another way, this magical land can tell the Land of the Emotional and the Land of the Automatic to relax and calm down.

In the cortex, or the Land of the Wise, the tools of cognition, learning, and working memory can help us manage the symptoms brought forth by anxiety, and reframe our responses to them accordingly. It is here where we can use the therapeutic tools of intention, awareness, and thought-management methods to exert control over the lower parts of our brain, thus keeping their wild tendencies in check.

This unique land plays an essential role in our understanding and treatment of the anxious brain.

While the thalamus, the amygdala, and all the other players are indeed a part of you, it wouldn’t make sense to believe that your identity as a whole is tied to any one of these characters. This detachment of one’s identity and behaviour from the physiological sensations of anxiety is a great place to start, and learning about the science of fear and anxiety helps tremendously.

While some people’s brains may have naturally higher baselines for anxiety and ruminative thought than others, the good news is that the brain is adaptable.

With enough intention and effort, anxiety-inducing thought patterns can be replaced with more realistic, healthy ones that keep us grounded in the present moment (2 Tim 1:7). This is where the Land of the Wise really shines, and is the only place equipped with the proper terrain and characters to help us do just that.

Adapted from a Blog by Lawrence Yeo (www.moretothat.com)

Have you thought about becoming a qualified counsellor? It’s a great opportunity to learn how you can extend God's love and grace to the hurting out in the community.

For those who would like to enrol in aifc’s accredited Christian counselling courses we have two intakes per year for courses commencing around the following months:

Enrolment Season - opens approximately 2 months prior to our courses commencing. Enrol online here during our enrolment season.

We also offer two modes of study:

A Master of Counselling course was introduced in 2018.